John Kennedy explains why knowing too much can harm your practice, and where you should apply your focus instead.

When I ask Chartered Accountants to make a list of the problems that hold them back from getting new clients, I am sometimes surprised at the issues they include. One point never makes the list, yet it is often a challenge – they just know too much.

How can that be a problem? Surely every client wants a highly knowledgeable accountant, someone who is on top of all of the details and knows all of the angles?This is partly true, but it hides how you can inadvertently damage your practice.

Unless you take time to step back, think clearly from the perspective of the client and shape your words to meet their needs, you can quickly lose their attention. This problem is compounded by the assumption that your clients pay you for your knowledge of accountancy, but that is not why clients pay you.

Why do clients pay you?

This is a deceptively simple question. Is it because of the things you know or because of the things you do for them? Or is it because your qualifications mean you are empowered to authorise documents? Each answer constitutes some part of the reason, but each also obscures a vitally important point.

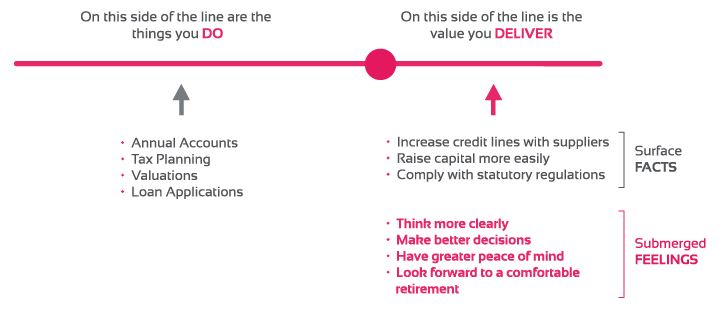

There are two crucial distinctions. First, clients do not pay you for the things you do; they pay you for the value you deliver. Second, the value you provide is only partially expressed in monetary terms. The fundamental truth is that, in many cases, clients most value the way you make them feel.

Where your real value lies

When you were studying as an undergraduate, the emphasis was on increasing your knowledge. You bought textbooks, you attended lectures, you completed assignments and the focus was always on what you knew – more facts, more information, more knowledge. Your exams tested and confirmed your knowledge; the more you could prove all you knew, the higher the grades. And the more you knew, the better you felt and the better you were regarded by the training firms for whom you hoped to work. With this relentless emphasis on knowing more and more, it is unsurprising that you came to assume that knowledge was where your value as an accountant lay.

Then you became a trainee Chartered Accountant in a firm. In your application, your interview and all of the tasks you were given, it was assumed that you had the knowledge required. At this point, the emphasis began to shift to the things you did. You were given specific tasks; what you did and the time it took was captured in timesheets. The emphasis of virtually every aspect of your work, your day and your value revolved around recording your activity in your timesheets.

And then you set up your own practice. By now, the emphasis had become so engrained – entrenched even – that you assumed that the key to building a successful practice revolved around turning what you knew into what you do, and recording that in timesheets to bill your client. This focus transferred to your client, but the truth is that this is not where your greatest value – nor your greatest opportunity – lies.

Your client wants your value, not your time

To build a successful practice, you need to move your thinking – and the focus for your client – beyond what you do and towards the value you provide. This involves two steps. The first step is to consciously move the emphasis from the things you do to the value you deliver. This first step is widely accepted but poorly implemented in practice.

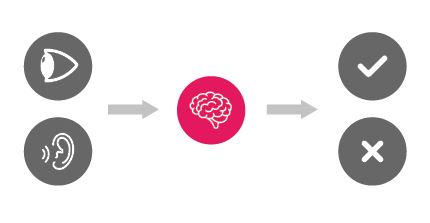

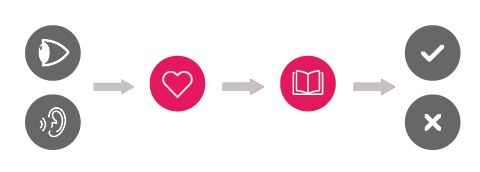

The second step is perhaps even more critical if much less understood. To build a practice with strong bonds with long-term clients, you need to move the emphasis from facts to feelings. Human beings like to believe that our species is more rational than it really is. We believe that we see or hear something, we analyse it rationally, and we decide. But do you suppress your feelings at work and give dispassionate advice? Are you always logical and provide clients with clearly thought-out analysis? This is what we like to believe, but it is often untrue.

The reality looks much more like this: we see or hear something; we filter it through our emotions; we interpret it and tell ourselves a story; and on that basis, we decide if it is right or wrong. This filtering process happens all the time and while every client wants the facts dealt with, they assume that this is the minimum level of service they will receive from their accountant.

The bonds that make clients work with you and generate referrals are forged beneath the level of conscious thoughts. Even in business, the way we feel is of enormous importance so you can create a genuine edge by understanding and applying this.

The positive feelings generated by your work include peace of mind, increased confidence in decision-making, or the anticipation of a comfortable retirement. These are important sources of value, yet few realise just how vital these submerged feelings are – even in the most dispassionate business transaction.

Every interaction has a submerged, and usually unstated, emotional aspect. As a practice owner, you must understand this and use it to your advantage. When making the shift in focus from the things you do to the value you deliver, you must take account of the genuine feelings at play.

Value is about more than money

Feelings are always there and are an important part of the value provided by a Chartered Accountant – no matter how much we try to convince ourselves that it is “just business”. Everyone has clients they like and clients they do not like; phone calls they look forward to making and phone calls they hate making; tasks they like doing and tasks they hate. We are very skilled at telling ourselves stories that turn these feelings into apparently rational explanations supported by facts to support our conclusions – but there is no avoiding the reality that feelings are very powerful, and this is the same for your client.

Let us take an example that shows just how powerful this concept is. Complete this sentence: “More than anything, I want my children to be…” I have used this example for decades and the answer is almost always “happy”. Occasionally, the respondent will say “content” or “fulfilled”, but in each case the answer is an emotion. It is never a financial or factual answer. This is a simple example of just how important feelings are.

How to gain an advantage

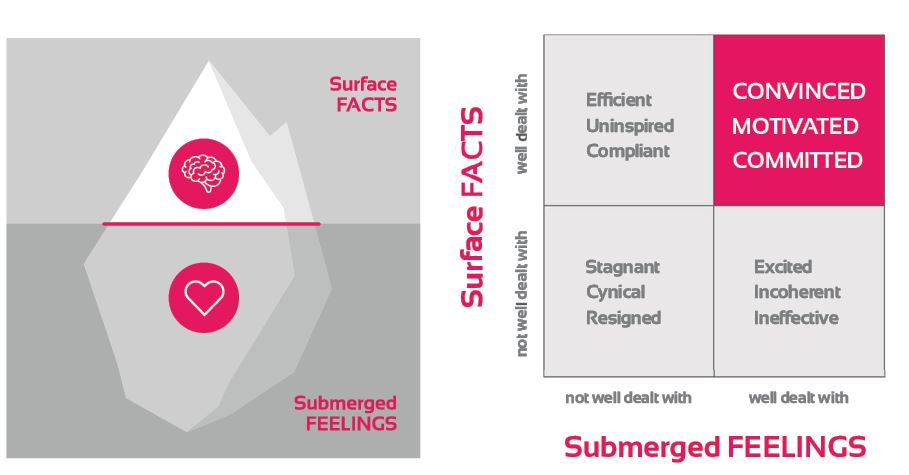

Gaining a client does not begin and end with you making clear all of the things you will do for them. For an individual to act, they must first feel confident that you understand what they want. And more importantly, they must also be convinced and motivated to the point that they are committed to working with you. Being convinced and motivated depends on your ability to address the feelings that so often remain submerged, unexamined, and unaddressed.

I have heard about all the effort accountants put into planning and preparing for meetings with potential clients, often spending hours crafting a well-designed and high-quality document and accompanying presentation. But they then go on to tell me that, even as they are discussing the document or giving the presentation, they know it is just not working.

Almost everyone has experienced this in some way, but many simply continue as if the submerged feelings are not there or are insignificant. The habitual pattern is to press on with more information, more facts, more details. The result is that you completely overlook the reality that the submerged feelings are the decisive factor in the ultimate success of any relationship.

It is much more useful to bring these feelings to the surface. You do this by using questions to draw out how the work you are discussing with your client will make them feel. The truth is that few clients care about exemplary management accounts or pristine submissions. Some do want to use their cash more effectively or to have a clear tax plan in place, but everyone wants to feel the peace of mind or sense of security that these actions bring.

Yet, many accountants spend too much time talking about the surface facts, the facts that – even when they are dealt with well – are, at best, efficient and uninspiring. The often-unacknowledged truth is that the feelings you create in your clients are just as valuable in building long-term relationships as the work you do. When you deal with the surface facts well, but the submerged feelings are left unattended, there is the illusion of progress, but the relationship is merely routine with little enthusiasm.

New clients in particular will sometimes engage you as part of their initial wave of enthusiasm, irrespective of the work you have done, but that will undoubtedly be a passing phase. The worst-case scenario is where the factual, practical aspects of the relationship are not adequately clarified and addressed, and the submerged feelings are also poorly dealt with. If this is the case, the client may accept you as a necessary evil, and you both bump along for a short time until your client moves to another practice. Even if they stay, these are the clients that are difficult to deal with, slow to pay, and frustrating to have.

Only when you take control of, and actively deal with, both the surface level factual tasks and the submerged feelings do relationships take off. When this happens, it is of real value to both you and your client. These are the client relationships you want – you are both in step, you both work well together, and you both feel positive about the work.

Too often, however, this kind of relationship is left to chance because the influential role of submerged feelings is seldom acknowledged, discussed, and actively addressed. But you can make these positive and rewarding client relationships a matter of choice. Just get into the habit of raising your clients’ understanding of the importance of the positive feelings generated by working constructively with you as their accountant. Ask about the areas they want to be confident in; probe how putting their affairs in order will reduce stress; and test and draw out the peace of mind they will get.

As you become skilled at eliciting and addressing these submerged feelings, you will set yourself apart from your competitors. Move your emphasis from what you do to the value it brings, and then take the critical step of drawing out and addressing the submerged feelings that are most important to your client.

John Kennedy is a strategic advisor. He has worked with leaders and senior management teams in a range of organisations and sectors.

LOADING...

LOADING...